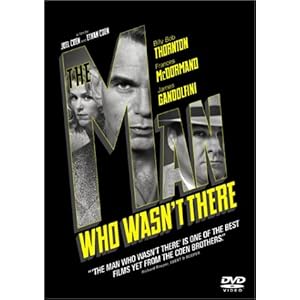

The Man Who Wasn't There is the Coen brothers' take on film noir, but like all of their work, it takes its inspiration in odd new directions. Because of its dedication to the filming style of older movies, matching the same sense of pace and a lot of the standards of where to point and focus the camera, it looks very old fashioned. You can still tell it's a more recent film though, even without the recognizable collection of excellent actors and Coen veterans that make up the cast, because there's just something weird about it. They're well known for the frequent nihilism of their plots, and Billy Bob Thornton's Ed Crane is so far into this mode that the film's been compared to The Stranger by Albert Camus, the ultimate existentialist novel.

The story starts like a lot of noir plots that go wrong in a hurry, with a relatively benign criminal scam. Crane is a barber, and he suspects that his wife, played by Frances McDormand, is sleeping with her boss, performed by James Gandolfini. After a customer tells him about his scheme to get rich with a new idea known as dry cleaning, Crane decides to make some money, and maybe get even while he's at it (although he really seems like he doesn't care that much about the affair), so he anonymously blackmails Gandolfini into leaving him the money to keep quiet. As expected though, things go very wrong, and people start dropping dead. Some bits are more predictable than others, but they do a good job of keeping things interesting, and things get a lot weirder after a certain point, eventually culminating in an ending that sort of feels like a fever dream that's actually happening.

It's an interesting story propped up further by the stellar look of the film (it was actually filmed in color and converted later to a beautiful black and white) and the outstanding performances by everyone involved. A lot of actors doing disaffected can just come off bored, but Thornton has mastered the art form. You really get inside his head and see what he does and doesn't care about (mostly he doesn't, you get the feeling that he truly doesn't mind the adultery and just tries the blackmail because he thinks it will work) with him having to say very little outside the narration. Gandolfini has to convey a lot of moods in not very many scenes and does it well, McDormand is just right for what the Coens are doing as usual, and Tony Shalhoub's lawyer is the perfect scumbag opportunist. Richard Jenkins and Scarlett Johannson are a father and daughter that don't have a lot of screen time, but Jenkins is excellent as a weary drunk and Johannson plays well off Thornton as the one thing he seriously seems concerned with. There are a lot of Coen trademarks, such as sudden and shocking bursts of violence and using similar imagery for scene transitions, but in some ways it's also unique for them, more restrained than usual and dedicated to matching the style they were after. They're still my favorite filmmakers, and this is one of their most intriguing projects.

AAAAAGGGHHHH

16 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment